GCD

Problems

Magic number

A3, 2015

A positive integer \(n\) is called a magic number if it has the following property: if \(a\) and \(b\) are two positive numbers that are not coprime to \(n\) then \(a+b\) is also not coprime to \(n\) For example, 2 is a magic number, because sum of any two even numbers is also even. Which of the following are magic numbers?

(i) 129

(ii) 128

(iii) 127

(iv) 100

Solution

Only 128 and 127 are magic numbers. See that \(n\) is a magic number if and only if \(n\) is a power of a prime.

Otherwise, write \(n=a b\) with \(a, b\) coprime.

Euclidean algorithm

B5, 2015

For an arbitrary integer \(n,\) let \(g(n)\) be the \(G C D\) of \(2 n+9\) and \(6 n^{2}+11 n-2 \). What is the largest positive integer that can be obtained as the value of \(g(n) ?\) If \(g(n)\) can be arbitrarily large, state so explicitly and prove it.

Solution

Long division gives \(6 n^{2}+11 n-2=(2 n+9)(3 n-8)+70 .\) By Euclidean algorithm, \(G C D\left(6 n^{2}+11 n-2,2 n+9\right)=G C D(2 n+9,70) .\) Thus \(g(n)\) divides \(70 .\) But since \(g(n)\) divides \(2 n+9,\) which is odd, \(g(n)\) divides \(35 .\) When \(n=13,2 n+9=35\) and hence \(g(13)=35 .\) Thus the maximum value of \(g(n)\) is \(35 .\)

Totient function

A3, 2016

Let \(\phi(n)\) denote the number of positive integers less than \(n\) that are relatively prime to \(n\). In other words, \(\phi(n)\) counts all \(m\) such that \(\operatorname{gcd}(m, n)=1\).

The number \(n=110179\) is a product of two primes \(p\) and \(q\). We also know that \(\phi(n) = 109480.\)

Find the values of \(p\) and \(q\).

Solution

Given \(n=p q=110179\). The number of integers relatively prime to \(n\) and smaller than \(n\) is \((p-1)(q-1) .\) So we have \(p q-p-q+1=109480 .\) We get \(p+q=700 .\) Now \(p, q\) are solutions to the quadratic \(x^{2}-700 x+110179\).

The discriminant of this quadratic is \(\sqrt{490000-440716}=\sqrt{49284}=222\). So we get \(p=\frac{700+222}{2}=461\) and \(q=\frac{700-222}{2}=239\).

GCD application

A7, 2016

We want to construct a nonempty and proper subset \(S\) of the set of non-negative integers. This set must have the following properties. For any \(m\) and any \(n\) if \(m \in S\) and \(n \in S\) then \(m+n \in S \quad\) and if \(m \in S\) and \(m+n \in S\) then \(n \in S\)

(i) 0 must be in \(S\).

(ii) 1 cannot be in \(S\).

(iii) There are only finitely many ways to construct such a subset \(S\).

(iv) There is such a subset \(S\) that contains both \(2015^{2016}\) and \(2016^{2015}\).

Solution

TTFF

Since the set \(S\) is nonempty, there is an element \(m \in S\). But then \(m=m+0\) and so \(0 \in S\).

1 cannot be in \(S,\) otherwise it will contain all non-negative integers.

By the division algorithm that if \(m, n\) are in \(S\) then so is their GCD. Therefore two coprime numbers cannot be in \(S .\) Otherwise their GCD, which is \(1,\) will be in \(S,\) a contradiction. It follows that such sets \(S\) are precisely those of the form \(n \mathbb{Z} \geq 0,\) the set of all non-negative multiples of a fixed non-negative integer \(n .\) So there are infinitely many such possible sets.

Sample a divisor

A4, 2017

Positive integers \(a\) and \(b,\) possibly equal, are chosen randomly from among the divisors of \(400 .\) The numbers \(a, b\) are chosen independently, each divisor being equally likely to be chosen. Find the probability that \(\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1\) and \(\operatorname{lcm}(a, b)=400\)

Solution

\(400=5^{2} \times 2^{4}\) has \((2+1) \times(4+1)=15\) factors, so total number of pairs \((a, b)\) is \(225 .\) For \(a, b\) to be coprime, they should have no prime factor in common and then their lcm is just their product, which is required to be \(400 .\) So there are only four allowed pairs:

(1,400),(400,1),(25,16) and (16,25).

The probability is \(\frac{4}{225}\).

Carrom board math

B6, 2018

Imagine the unit square in the plane to be a carrom board. Assume the striker is just a point, moving with no friction (so it goes forever), and that when it hits an edge, the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence, as in real life. When it hits another edge it bounces again similarly and so on. If the striker ever hits a corner it falls into the pocket and disappears. The trajectory of the striker is completely determined by its starting point \((x, y)\) and its initial velocity \(\overline{(p, q)}\)

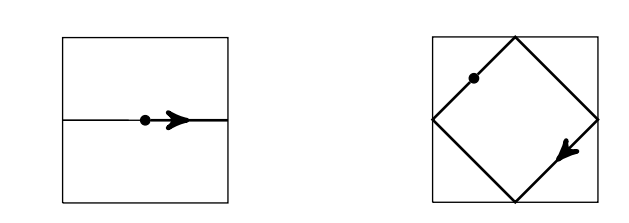

If the striker eventually returns to its initial state (i.e. initial position and initial velocity), we define its bounce number to be the number of edges it hits before returning to its initial state for the first time. For example, the trajectory with initial state \([(.5, .5) ;(1,0)]\) has bounce number 2 and it returns to its initial state for the first time in 2 time units. And the trajectory with initial state \([(.25, .75) ;(1,1)]\) has bounce number 4

(a) Suppose the striker has initial state \([(.5, .5) ;(p, q)] .\) If \(p> q \geq 0\) then what is the velocity after it hits an edge for the first time? What if \(q> p \geq 0 ?\)?

(b) Draw a trajectory with bounce number 5 or justify why it is impossible.

(c) Consider the trajectory with initial state \([(x, y) ; \overline{(p, 0)}]\) where \(p\) is a positive integer. In how much time will the striker first return to its initial state?

(d) What is the bounce number for the initial state \([(x, y) ; \overline{(p, q)}]\) where \(p, q\) are relatively prime positive integers, assuming the striker never hits a corner?

Solution

(a) If \(p> q\) then the striker will hit the vertical edge first, and its new velocity will be \((-p, q) .\) If \(p< q\) then the striker will hit the horizont al edge first, and its new velocity will be \(\overline{(p,-q)}\)

(b) No, it is not possible. If the striker has bounce number \(5,\) then it must have an odd number of vertical edge bounces or horizontal edge bounces. In the former case, when the striker returns to its initial state, the \(x\) -component of its velocity will be wrong, by the formula in part \((a)\). In the latter case the \(y\) component will be wrong.

(c) It will take \(\frac{2}{p}\) time to return to its initial state.

(d) The bounce number is \(2 p+2 q\). At time \(2,\) the striker will have completed \(p\) horizontal round-t rips and \(q\) vert ical round trips, and will have returned to its init ial state. To see this, recall from part (c) that it will take time \(\frac{2}{p}\) for each horizontal round trip and time \(\frac{2}{q}\) for each vertical round trip. since \(p\) and \(q\) are relatively prime, it will only be at time 2 that an int eger number of vertical and horizontal round trips have been completed.

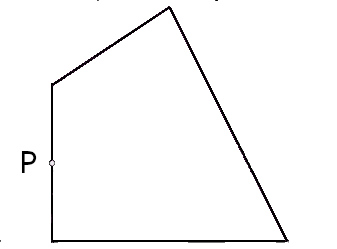

Shortest cycle on a carrom board

Suppose we had a carrom board shaped as a quadrilateral as shown below. The striker is at position P. We want to strike it so that it rebounds off the walls and returns to the starting position. At the same time, the length of the path that it traces before returning to P must be minimum. At which angle should we strike?

Watch this Youtube video by Zach Star, where he discusses an elegant solution to this problem. The problem seems to require calculus, but has a nice geometric solution.