Triangles

Problems

- Possible triangles

- Midpoint of a median

- Isoceles triangle

- A chord within a rectangle

- Non-congruent triangles with fixed perimeter

- Triangle construction

- Segments inside a triangle

- Rhombus within a triangle

- Rational triangle

- Triangle with segments

- Matching pairs of points

- Red-blue points

- Square inside a hexagon

- Triangle in a square

- Midpoints of a quadrilateral

- Specific midpoints

Possible triangles

A3, 2021

\(ABC\) is a triangle such that \(AB=1\) cm and \(\angle CAB = 20.21^{\circ}\). Let \(N(x)\) denote the number of non-congruent triangles such that \(BC=x\) cm, where \(x\) is a positive real number. There exists an \(x\) such that:

(a) \(N(x)=0\).

(b) \(N(x)=1\).

(c) \(N(x)=2\).

(d) \(N(x)=3\).

Solution

(a) True.(b) True.

(c) True.

(d) False.

Explanation. Consider the line \(l\) that passes through \(A\) at an angle \(20.21^\circ\) to \(AB\). Let the length of the shortest distance from \(l\) to \(B\) be \(d\). If \(x< d\) there is no solution. If \(x=d\) there is exactly one solution. If \(1>x>d\), there are two solutions.

Midpoint of a median

B2, 2010

Take a triangle ABC and draw BE as a median. Suppose M is the mid-point of BE. The line passing through points A and M meets BC at D. What is the ratio AM:MD?

Hint: Draw a line from E that is parallel to AD.

Solution

The hint gives away the problem. We solve the problem by using similarity of triangles.

(i) \( \triangle ADC \sim \triangle EFC \)

Equality AE = EC \(\implies\) AC=2EC \(\implies\) AD=2EF.

(ii) \( \triangle BMD \sim \triangle BEF \)

Equality BM = ME \(\implies\) MD=EF/2.

From (i) and (ii), we have 4MD=AD. So, the ratio AM:MD=3.

Isoceles triangle

B1, 2013

In triangle PQR, the bisector of angle P meets side QR in point D and the bisector of angle Q meets side PR in point E. Given that DE is parallel to PQ, show that PE = QD and that the triangle PQR is isosceles.

Solution

Claim. \(\angle E P D=\angle D P Q=\angle E D P\)

Proof. The first equality comes from the problem statement.

Consider the second equality. Alternate angles made by line \(P D\) intersecting parallel lines \(D E\) and \(P Q\) are equal. Thus \(\triangle E P D\) is isosceles with \(E P=E D \). Similarly \(E D=D Q\) using the fact that \(Q E\) bisects \(\angle D Q P\) also intersects parallel lines \(D E\) and \(P Q\). Therefore \(E P=\) \(E D=D Q .\) Now by the basic proportionality theorem, \(\frac{R E}{E P}=\frac{R D}{D Q} .\) As the denominators \(E P\) and \(D Q\) are equal, the numerators must be equal as well, i.e., \(R E=R D .\) Finally, \(R P=R E+E P=R D+D Q=R Q,\) so \(\triangle P Q R\) is isosceles.

A chord within a rectangle

A2, 2011

In a rectangle ABCD, the length BC is twice the width AB. Pick a point P on side BC such that the lengths of AP and BC are equal. The measure of angle CPD is

- \(75^{\circ}\)

- \(60^{\circ}\)

- \(45^{\circ}\)

- none of the above

Solution

Let the length of AB be one unit and BC be two units, respectively. We draw a perpendicular from vertex P to X. Since APX is a right angled triangle: \begin{align} AX^2 &= AP^2 - PX^2 \\\\ AX^2 &= 2^2 - 1^2 \\\\ AX &= \sqrt{3} \\\\ \end{align} Hence, the length of CP is \( 2-\sqrt{3} \). The angle CPD is \( \arctan \frac{1}{CP} = \arctan \frac{1}{2 - \sqrt{3}} \) . We can verify that the answer is \( 75^{\circ} \).

Non-congruent triangles with fixed perimeter

A8, 2018

How many non-congruent triangles are there with integer lengths \(a \leq b \leq c\) such that \(a+b+c=20 ?\)

Solution

It is clear that \(1< a \leq b \leq c<10\). Now, \(c< a+b\) and \(c=20-a-b\) implies \(10< a+b ;\) this also means that \(b \geq a\) and \(b \geq 11-a\). Moreover, we also have \(b \leq 20-a-b .\) One can further conclude that \(a \leq 6,\) otherwise \(7 \leq b \leq 6 .\) So as \(a\) ranges from 2 to 6 we have that \(b\) takes the following values \(a=2, b=9 ; a=3, b=\) \(8 ; a=4, b \in\{7,8\} ; a=5, b \in\{6,7\} ; a=6, b \in\{6,7\} .\) The total number of possible triangles is 8.

Triangle construction

A10, 2014

In each of the following independent situations we want to construct a triangle \(A B C\) satisfying the given conditions. In each case state state how many such triangles \(A B C\) exist up to congruence.

(i) \(A B=30 \quad B C=95 \quad A C=55\).

(ii) \(\angle A=30^{\circ} \quad \angle B=95^{\circ} \quad \angle C=55^{\circ}\).

(iii) \(\angle A=30^{\circ} \quad \angle B=95^{\circ} \quad B C=55\).

\((\mathrm{iv}) \angle A=30^{\circ} \quad A B=95 \quad B C=55\).

Solution

- None. The triangle inequality fails since \(AB+AC< BC\).

- \(\infty\). The angles sum to \(180^{\circ}\) and triangle of any scale is possible.

- 1.

- 2. Draw a line segment \(AB\) with the given length. Consider the line passing through \(A\) and making \(30^\circ\) with \(AB\). If we draw a circle with center as \(B\), it touches the line at two points (see Fig. below). Hence, there are two choices for the vertex \(C\).

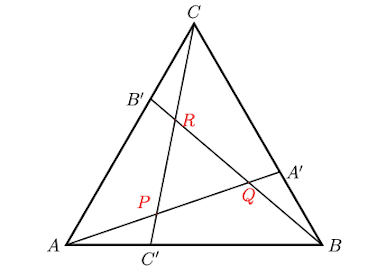

Segments inside a triangle

B4, 2018

Let \(A B C\) be an equilateral triangle with side length \(2 .\) Point \(A^{\prime}\) is chosen on side \(B C\) such that the length of \(A^{\prime} B\) is \(k<1\). Likewise points \(B^{\prime}\) and \(C^{\prime}\) are chosen on sides \(C A\) and \(A B\) with \(A C^{\prime}=C B^{\prime}=k\). Line segments are drawn from points \(A^{\prime}, B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}\) to their corresponding opposite vertices. The intersections of these line segments form a triangle, labeled \(P Q R\) in the interior. Show that the triangle \(P Q R\) is an equilateral triangle with side length \(\frac{4(1-k)}{\sqrt{k^{2}-2 k+4}}\).

Solution

Note that triangles \(A B A^{\prime}, C A C^{\prime}\) and \(B C B^{\prime}\) are congruent by the SAS test. Triangles \(B A^{\prime} Q, C B^{\prime} R\) and \(A C^{\prime} P\) are a lso congruent. By using the property of opposite angles we get that all the three angles of the triangle \(P Q R\) are the same. Hence it is an equilateral triangle. Dropping the perpendicular bisector \(A O\) on the side \(B C\) we get the following : \[ \begin{aligned} A A^{\prime 2} &=A O^{2}+A^{\prime} A^{2} \\ &=(1-k)^{2}+(\sqrt{3})^{2} \\ &=k^{2}-2 k+4 \end{aligned} \] Observe that triangles \(A B A^{\prime}\) and \(B Q A^{\prime}\) are similar by the AAA test: \(A^{\prime} Q B\) and \(A^{\prime} B A\) are 60 degrees and \(A^{\prime} B Q\) and \(A^{\prime} A B\) are corresponding angles. Therefore: \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{A B}{B Q} &=\frac{B A^{\prime}}{Q A^{\prime}}=\frac{A^{\prime} A}{A^{\prime} B} \\ \frac{2}{B Q} &=\frac{k}{Q A^{\prime}}=\frac{\sqrt{k^{2}-2 k+4}}{k} \\ B Q &=\frac{2 k}{\sqrt{k^{2}-2 k+4}} \\ Q A^{\prime} &=\frac{k^{2}}{\sqrt{k^{2}-2 k+4}} \end{aligned} \] Now using \(A A^{\prime}=A P+P Q+Q A^{\prime}\) we get \[ P Q=\frac{4(1-k)}{\sqrt{k^{2}-2 k+4}} \]

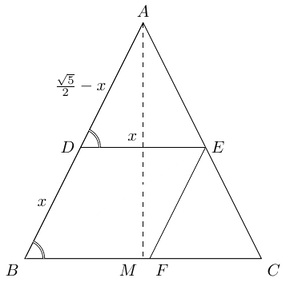

Rhombus within a triangle

A12, 2010

In an isoceles triangle ABC with A at the apex, the height and the base are both equal to 1cm. Points D, E and F are chosen from each side such that BDEF is a rhombus. Find the length of the side of this rhombus.

Solution

We want to find the side length of the rhombus \(BDEF\). We will find the length of \(AB\) first. Let \(M\) be the mid-point of \(BC\). So \(BM=1/2\,\mbox{cm}\). We know that \( AM = BC = 1\,\mbox{cm}\). By applying Pythagoras theorem to \(\Delta ABM\), we get \(AB = \sqrt{BM^2 + AM^2} = \frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\).

Solution due to Aryan Komarla.

Rational triangle

B4, 2010

If all the sides and area of a triangle were rational numbers then show that the triangle is got by ‘pasting’ two right-angled triangles having the same property.

Solution

Let ABC be a triangle with rational sides and rational area. Let \( B\) be the largest angle.

Try this. Prove that any rational triangle can be split into two rational triangles one of which is similar to the original one.

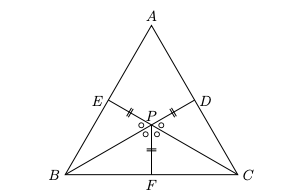

Triangle with segments

A10, 2016

You are given a triangle ABC, a point D on segment AC, a point E on segment. AB and a point F on segment BC. Let BD and CE intersect in point P. Join P with F. Suppose that the following is true:

\(\angle\)EPB=\(\angle\)BPF=\(\angle\)FPC=\(\angle\)CPD and PD=PE=PF. An indicative triangle is shown below, there could be other triangles too.

- (i) AP must bisect \(\angle\) BAC.

- (ii) \(\triangle\) ABC must be isosceles.

- (iii) A, P, F must be collinear.

- (iv) \(\angle\) BAC must be \(60^{\circ}\)

Solution

TFFT

(i) BP and CP are angle bisectors meeting at P, so AP bisects \(\angle\)A since the angle bisectors are concurrent.

(iv) The angles marked with symbol o at point P are all \(60^{\circ}\) because \(\angle\)EPD is twice this common value. It follows that half the sum of \(\angle\)B and \(\angle\)C is \(60^{\circ}\). So \(\angle\)A is \(60^{\circ} \).

The others are false, in fact check that any triangle with \(\angle A=60^{\circ},\) angle bisectors BD and CE, their point of intersection P and PF bisecting \(\angle\)BPC will satisfy the given data.

Matching pairs of points

B6a, 2012

For \(n>1\), a configuration consists of \(2 n\) distinct points in a plane, \(n\) of them red, the remaining \(n\) blue, with no three points collinear. A pairing consists of \(n\) line segments, each with one blue and one red endpoint, such that each of the given \(2 n\) points is an endpoint of exactly one segment. Prove the following. a) For any configuration, there is a pairing in which no two of the \(n\) segments intersect. (Hint: consider total length of segments.)

Solution

For any configuration, there are only finitely many pairings. Choose one with least possible total length of segments. Here no two of the \(n\) segments can interest, because if \(R B\) and \(R^{\prime} B^{\prime}\) intersect in point \(X\) then we get a contradiction as follows. Using triangle inequality in triangles \(R X B^{\prime}\) and \(R^{\prime} X B,\) we get \(R B^{\prime}+R^{\prime} B<R B+R^{\prime} B^{\prime}\) (draw a picture). So replacing \(R B\) and \(R^{\prime} B^{\prime}\) with \(R^{\prime} B\) and \(R B^{\prime}\) would give a pairing with smaller total length.

Red-blue points

B6b, 2012

Given \(n\) red points (no three collinear), we can place \(n\) blue points such that any pairing in the resulting configuration will have two segments that do not intersect.

Solution

Given \(n\) red points, find a triangle \(A B C\) such that \(A\) is a red point and all other red points are inside triangle \(ABC\). This is always possible since \(B\) and \(C\) can be placed anywhere, as long as \(ABC\) is a triangle. Place one blue point at \(B\) and \(n-1\) blue points at \(C\). This will ensure that there will be a non-intersecting pair of lines involving vertex \(A\).

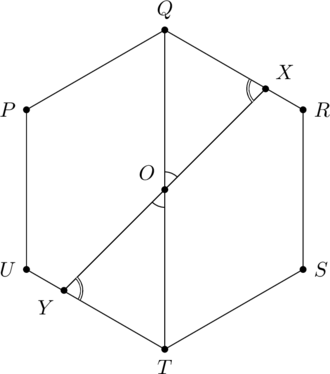

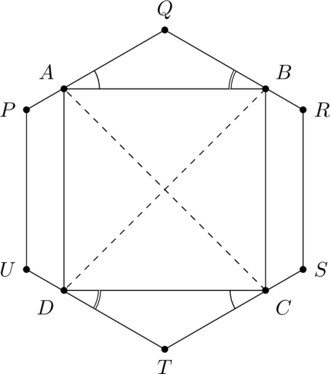

Square inside a hexagon

B6, 2017

You are given a regular hexagon. We say that a square is inscribed in the hexagon if it can be drawn in the interior such that all the four vertices lie on the perimeter of the hexagon.

- (a) A line segment has its endpoints on opposite edges of the hexagon. Show that it passes through the center of the hexagon if and only if it divides the two edges in the same ratio.

- (b) Suppose a square \(A B C D\) is inscribed in the hexagon such that \(A\) and \(C\) are on the opposite sides of the hexagon. Prove that center of the square is same as that of the hexagon.

- (c) Suppose the side of the hexagon is of length \(1 .\) Then find the length of the side of the inscribed square whose one pair of opposite sides is parallel to a pair of opposite sides of the hexagon.

- (d) Show that, up to rotation, there is a unique way of inscribing a square in a regular hexagon.

Solution

(a) Suppose the segment \(XY\) meets opposite sides \(QR\) and \(TU\) of the hexagon. Let \(O\) be the midpoint of \(XY\). In the figure below, the midpoint of the chord must pass through the center. We show that if \(\frac{QX}{XR}=\frac{TY}{YU}\), then \(O\) is the center of the hexagon.

Consider triangles \(OXQ\) and \(OTY\). By the \(ASA\) postulate they are congruent. So, \(QO=OT\). Therefore, \(O\) is the midpoint of \(QT\), which makes it the center of the hexagon. The other direction can be proved with a similar argument.

(b) Suppose we have inscribed a square \(A B C D\) in a hexagon \(P Q R S T U\), as shown in the figure below. In the previous problem, we proved that a chord that cuts the opposite sides of the hexagon in equal ratios must pass through the center of the hexagon. Here we show that the diagonals of the square are chords that satisfy that property. This will imply that both diagonals pass through the center of the hexagon.

The diagonals of the square pass through the center of the hexagon. We have used the result of the previous problem.

Lemma. \(\triangle A Q B \cong \triangle C T D \)

Proof. We know that \(PQ \| S T\) and \(A C\) is a transversal. So \(\angle Q A C=\angle T C A\), also \(\angle B A C=\angle D C A=45^{\circ} \). So \(\angle Q A B=\angle D C T\). Similarly, \(\angle Q B A=\angle C D T\). Also, \(\angle A Q B=\angle C T D,\) since they are angles in a regular hexagon. Moreover, \(A B=C D\). As a result we get that \(\triangle Q B A \cong\) \(\triangle T D C.\;\;\;\;\) \(\square\)

So we have \(Q B=T D\) and \(Q A=T C\). This in turn implies that \(B R=D U\) and \(P A=C S\). Thus, \[ \frac{Q B}{B R}=\frac{T D}{D U} \text { and } \frac{P A}{A Q}=\frac{S C}{C T} \]

(c) In the figure above, let \(PA=x\) and \(AQ=1-x\). The vertical distance between \(A\) and \(P\) is \(x\sin 30^\circ\). So, \[ AD = 2x\sin 30^{\circ} + 1 = x+1 \] Also, we have \(AB=2AQ\sin 30^\circ\). \[ AB = \sqrt{3}(1-x) \] Since \(AB=AD\), we have \(x = (\sqrt{3}-1)/(\sqrt{3}+1) \). Hence, the side of the square is \(AD=x+1=\sqrt{3}(\sqrt{3}-1)\) units.

(d) Suppose the square \(ABCD\) is inscribed in a regular hexagon \(PQRSTU\). The positions of \(A\) and \(B\) on \(PQ\) and \(QR\), respectively, determine the square. If there was a square other than the one shown in the figure above, we would have \(|QA|\neq |QB|\). Without loss of generality, assume that \(|QA|>|QB|\). Let \(O\) be the center of the hexagon and the square. We have proved that the centers coincide in part (b). Since \(O\) is the center of \(ABCD\), we have \(|OA|=|OB|\). Let \(A^\prime\) be a point on \(QR\) such that \(|QA|=|QA^\prime|\). Due to symmetry, \(|OA|=|OA^\prime|\) which implies that \(|OA^\prime|=|OB|\). Thus, \(\triangle B O A^{\prime}\) is isosceles. Let \(\angle QAB=\alpha\) and \(\angle QBA=\beta\). Since \(\angle AQB = 120^\circ\), we have \(\alpha+\beta=60^\circ\). \begin{align*} 180^{\circ}&=\angle O B A^{\prime}+\angle O B Q \\ &=\angle O B Q+\angle O A^{\prime} B=\angle O B Q+\angle O A Q \\ &=45^{\circ}+\beta+45^{\circ}+\alpha \end{align*} so \(\alpha+\beta=90^{\circ},\) a contradiction since \(\alpha+\beta=60^{\circ}\).

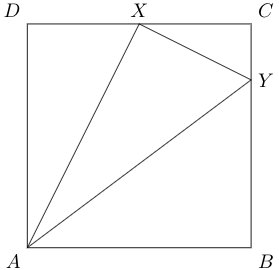

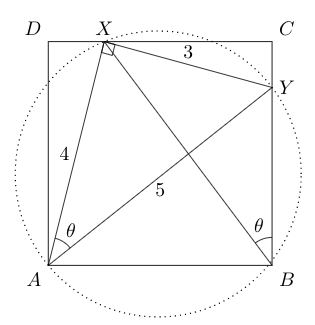

Triangle in a square

B1b, 2021

\(ABCD\) is a square. Point \(X\) lies on a circle with \(AY\) as the diameter. Points \(X\) and \(Y\) lie on the sides of the square such that \(AX=4\) cm and \(AY=5\) cm. What is the area of the square \(ABCD\)?

Solution I via cyclic quadrilateral

Sol. due to Abhishek Goel.

Since \( \angle AXY + \angle ABY = 180^{\circ} \), \(AXYB\) is a cyclic quadrilateral. Suppose the chord \(XY\) subtends an angle \(\theta\) at \(A\) and \(B\) as shown:

Solution II via similar triangles

\begin{align*} \angle DAX &= \angle CXY\\ \implies \Delta DAX &\sim \Delta CXY \\ \frac{XY}{AX} &= \frac{XC}{AD} \\ \frac{3}{4} &= \frac{XC}{AD} \\ XC &= \frac{3}{4} AD \\ DX &= CD-CX = \frac{1}{4}AD\\ AD^2+DX^2 &= 4^2\\ AD^2+\frac{AD^2}{16} &= 16\\ AD &= \frac{16}{\sqrt{17}}\\ \text{Area of the square} &= \frac{256}{17} \end{align*} Problem source: Presh Talwalkar's channel.Midpoints of a quadrilateral

B2a, 2012

Consider a convex quadrilateral \({ABCD}\). Let \({E}, {F}, {G}\) and \({H}\) be the midpoints of the sides \({AB}, {BC}, {CD}\) and \({DA}\), respectively. Show that \({EFGH}\) is a parallelogram whose area is half that of \({ABCD}\).

Solution

Lemma. \(EFGH\) is a parallelogram.

Proof. Consider the diagonal \(AC\). By the basic proportionality theorem:

- \({EF}\) and \({AC}\) are parallel.

- \({AC}=2 {EF} \)

- \(\Delta ABC \sim \Delta EBF\).

A similar argument to diagonal \(BD\) implies the lemma. \(\quad\square\)

Let \((X)\) denote the area of shape \(X\).

\begin{align} (ABCD) = (ABC) + (ACD) \\ 1/2 \cdot (ABCD) = (EFB) + (HGD) \end{align}

By applying the above argument to the diagonal \(BD\) and triangles \(CFG\) and \(AEH\), we get the following:

\begin{align} (ABCD) = (ABD) + (BCD) \\ 1/2\cdot (ABCD) = (CFG) + (AEH) \end{align}

Together we get:

\begin{align} 1/2\cdot (ABCD) &= (CFG) + (AEH) + (EFB) + (HGD) \\ (EFGH) &= \frac{1}{2} (ABCD) \end{align}

Specific midpoints

B2b, 2012

Let \(E=(0,0)\), \(F=(0,-1)\), \(G=(1,-1)\) and \(H=(1,0)\). Find all points \({A}=(p, q)\) in the first quadrant such that \({E}, {F}, {G}\) and \({H}\) respectively are the midpoints of the sides \({AB}\), \({BC}, {CD}\) and \({DA}\) of a convex quadrilateral \({ABCD}\).

Solution

Let us draw the square \(EFGH\) on the coordinate plane (see the figure below). From the previous problem we know that the diagonals of \(ABCD\) must be parallel to the axes. Suppose the two diagonals lie on the lines \(x=p\) and \(y=-q\), respectively. Since the diagonals pass through \(EFGH\), we must have \( p\in (0,1) \) and \( q\in(0,1) \).

Notation. Let \(\mbox{proj}_x PQ\) (resp. \(\mbox{proj}_y PQ\)) denote the length of the projection of segment \(PQ\) on the \(x\)-axis (resp. \(y\)-axis).

Lemma 1. The coordinates of vertices \(A\) and \(B\) are \( (p,q) \) and \( (-p,-q) \), respectively.

Since \(E\) is the mid-point of \(AB\), we have \(|AE|=|BE|\).

\begin{align*} \mbox{proj}_y BE &= q = \mbox{proj}_y AE \implies A=(p,q) \\ \mbox{proj}_x AE &= p = \mbox{proj}_x BE \implies B=(-p,-q) \quad\square \end{align*}

Lemma 2. The coordinates of vertices \(C\) and \(D\) are \( (p,2-q) \) and \( (2-p,-q) \), respectively.

Let us calculate the \(y\)-coordinate of \(C\) first. Since \(F\) is the mid-point of \(BC\) we have \(|BF|=|CF|\).

\begin{align*} \mbox{proj}_y BF &= 1-q = \mbox{proj}_y CF \implies C=(p,2-q) \\ \end{align*}

Now we calculate the \(x\)-coordinate of \(D\). Since \(G\) is the mid-point of \(CD\) we have \(|CG|=|GD|\).

\begin{align*} \mbox{proj}_x CG &= 1-p = \mbox{proj}_x GD \implies D=(2-p,-q) \quad\square \end{align*}

From the above lemmas we infer that once the diagonals are fixed, the quadrilateral \(ABCD\) also gets fixed. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the pair of numbers \( (p,-q) \) and the quadrilateral \(ABCD\). The vertex \(A\) can take a value \((p,q)\) with \(p\in(0,1) \) and \(q \in (0,1) \). The set of all possible points for vertex \(A\) is shaded in the above figure.