Circles [11]

Problems

- Circle inside a triangle inside a circle

- Progression of circles

- Circumcenter and orthocenter

- Cyclic polygon

- Cyclic trapezoids

- Intersecting circles

- Interior point in a parallelogram

- Quadrilateral with circles

- On Ceva’s theorem

- Straight-edge construction

- Straight-edge with circle

- An old Russian problem

Circle inside a triangle inside a circle

A1, 2017

Consider the following construction in a circle. Choose points \(A, B, C\) on the given circle such that \(\angle A B C\) is \(60^{\circ}\) and \(A B=B C\). Draw another circle that is tangential to the chords \(A B, B C\) and to the original circle. Do the above construction in the unit circle to obtain a circle \(S_{1}\). Repeat the process in \(S_{1}\) to obtain another circle \(S_{2} .\) What is the radius of \(S_{2}\)?

Solution

Consider the center \(\mathrm{O}\) and diameter \(\mathrm{BD}\) of the unit circle. It is easy to see that \(S_{1}\) passes through \(D\) and its center \(E\) lies between \(O\) and \(D .\) Let \(r\) be the radius of \(S_{1},\) so length of \(\mathrm{ED}\) is \(r .\) Consider the perpendicular from \(\mathrm{E}\) to chord \(\mathrm{BA}\), meeting \(\mathrm{BA}\) in point \(\mathrm{F}\). Then length of \(\mathrm{EF}\) is also \(r\) and therefore in the \(30-60-90\) triangle \(\mathrm{BEF}\), the length of the hypotenuse \(\mathrm{BE}\) is \(2 r .\) Thus \(2=\mathrm{BD}=\mathrm{BE}+\mathrm{ED}=3 r,\) thus \(r=\frac{2}{3} .\) By similarity, the radius of \(S_{2}\) is \(\frac{2}{2} \times \frac{2}{2}=\frac{4}{a}\)

Progression of circles

A1, 2018

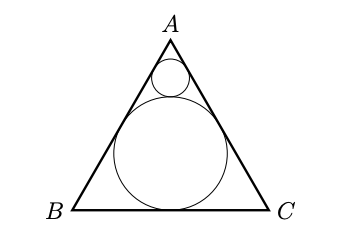

Consider an equilateral triangle \(A B C\) with altitude 3 centimeters. A circle is inscribed in this triangle, then another circle is drawn such that it is tangent to the inscribed circle and the sides \(A B, A C .\) Infinitely many such circles are drawn; each tangent to the previous circle and the sides \(A B, A C .\) The figure shows the construction after 2 steps. Find the sum of the areas of all these circles.

Solution

Let us calculate the radius of the largest inscribed circle.

Hence, the size of the largest circle is 1 cm. The next triangle's base passes through point P. We know that AP=1 cm, which is 1/3rd the size of the altitude of the original triangle. Hence, the next circle that is inscribed is 1/3rd the size of the largest circle. The radii follow a geometric progression.

Let \(A\) denote the total area of these circles then: \[ \begin{aligned} A &=\pi(1)^{2}+\pi(1 / 3)^{2}+\pi(1 / 9)^{2}+\cdots \\ &=\pi+\pi(1 / 3)^{2}\left[1+(1 / 3)^{2}+(1 / 9)^{2}+\cdots\right] \\ &=\pi+(1 / 9) A \\ &=(9 / 8) \pi \end{aligned} \]

Circumcenter and orthocenter

A3, 2013

Let \(S\) be a circle with center O. Suppose \(A, B\) are points on the circumference of \(S\) with \(\angle A O B=120^{\circ}\). For triangle \(A O B,\) let \(C\) be its circumcenter and \(D\) its orthocenter (i.e., the point of intersection of the three lines containing the altitudes). For each statement below, write whether it is TRUE or FALSE.

- The triangle \(A O C\) is equilateral.

- The triangle \(A B D\) is equilateral.

- The point \(C\) lies on the circle \(S\).

- The point \(D\) lies on the circle \(S\).

Solution

All the statements are true. Consider the figure shown below. The bisector of \(\angle A O B\) splits this angle into two angles of \(60^{\circ}\) each and meets the circle, at point \(C^{\prime} \).

Cyclic polygon

A11, 2014

Let \(A_{n}=\) the area of a regular \(n\) -sided polygon inscribed in a circle of radius 1 (i.e., vertices of this regular \(n\) -sided polygon lie on a circle of radius 1 ). (i) Find \(A_{12}\). (ii) Find \(\left\lfloor A_{2014}\right\rfloor,\) i.e., the greatest integer \(\leq A_{2014}\)

Solution

The area of an \(n\)-sided regular polygon is given by \[ A = \frac{nr^2}{2} \sin \left( \frac{2\pi}{n} \right) \]

(i) \( A_{12} = 6 \sin(\pi/6 ) = 3\).

(ii) 3. \( A_{2014} = 1012 \sin(\pi/1012) \approx \pi \), since for small values of \(x\), \(\sin x \approx x\).

Another way to reason is to observe that a polygon with many sides is approximately close to a circle. Since the area of the circle is \(\pi\), the polygon's area must also be close to \(\pi\).

Cyclic trapezoids

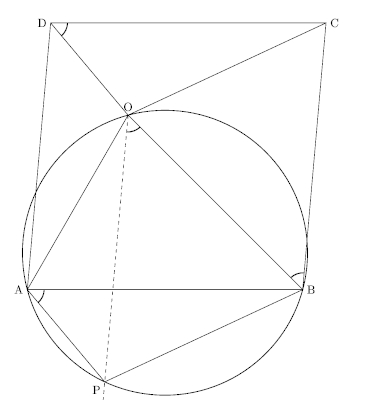

B1, 2020

We have four cyclic points \(A\), \(B\), \(C\) and \(D\). \(AC\) and \(BD\) are the diameters of the circle. \(AB =12 \)cm and \(BC = 5\)cm. \(P\) is a point on the arc joining \(A\) & \(B\) which does not contain \(C\) and \(D\). \(AP = a\), \(BP = b\), \(CP = c\) and \(DP = d\). Find \(\frac {a+b}{c+d}\) and \(\frac {a-b}{d-c}\).

Solution

Since \(AC\) and \(DB\) are diameters, \( \angle ABC \) and \( \angle DAB \) must be right angles. Hence, \(ABCD\) is a rectangle with a diagonal whose length is 13 cm.

Applying Ptolemy's theorem to trapezoids \(APBC\) and \(APBD\), we get the following two equations, respectively.

\begin{align} 12c = 13b + 5a \\ 12d = 13a + 5b \end{align}

Adding the two equations, we get \( 12(c+d) = 18(a+b) \). \[ \boxed{ \frac{a+b}{c+d} = \frac{2}{3} } \] Since \(DB\) is a diameter, \( \angle DPB = 90^\circ \). Similarly, since \(AC\) is a diameter, \(\angle APC=90^\circ \). Applying Pythagoras theorem to triangles \(DPB\) and \(APC\) we get: \begin{align} b^2 + d^2 = 13^2 \\ a^2 + c^2 = 13^2 \end{align} \begin{align} a^2 - b^2 &= d^2 - c^2 \\ (a+b)(a-b) &= (d-c)(d+c) \\\\ \frac{a-b}{d-c} &= \frac{c+d}{a+b} \end{align} \[ \boxed{ \frac{a-b}{d-c} = \frac{3}{2} } \]Reference

This problem appears in the book titled Problems in plane geometry by I.F.Sharygin (1982). It was part of a delightful series called Science for everyone by MIR publishers.

See: Page 39, Section 1, Problem 183.

Intersecting circles

B6, 2010

Two circles of equal radii \(r\) pass through each others centers. Prove that the area of the overlapping region is \( \frac{r^2}{6}(4\pi - \sqrt{27})\).

Solution

The radius of each circle is \(r\). The required common area is same as twice the area of the sector ACD minus the area of the rhombus ACBD. The rhombus ACBD is made up of two equilateral triangles so its area is \( 2\times \frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\times r^2 \).

Interior point in a parallelogram

B4, 2019

Let \(A B C D\) be a parallelogram. Let \(O\) be a point in its interior such that \(\angle A O B+\) \(\angle D O C=180^{\circ} .\) Show that \(\angle O D C=\angle O B C\).

Solution

Key idea. Translate the triangle \(DOC\).

Fact. If the opposite angles of a quadrilateral sum to \(180^\circ\), the vertices must be cyclic.

\begin{align*} \angle AOB + \angle DOC& =180^{\circ} \mbox{(Given)} \\ \implies \angle AOB + \angle APB & =180^{\circ} \end{align*} Hence, \(APBO\) must be a cyclic quadrilateral. The rest of the proof is by angle-chasing. \begin{align*} \angle PAB &= \angle POB \;\mbox{ since the chord \(PB\) subtends them} \\ \angle OBC &= \angle POB \;\mbox{ since } OP \parallel BC \\ \angle OBC &= \angle POB = \angle PAB = \angle ODC \end{align*}

Quadrilateral with circles

B6a, 2014

Two circles \(G_{1}, G_{2}\) intersect at points \(X, Y\). Choose two other points \(A, B\) on \(G_{1}\) as shown in the figure. The line segment from \(A\) to \(X\) is extended to intersect \(G_{2}\) at point \(L\). The line segment from \(L\) to \(Y\) is extended to meet \(G_{1}\) at point \(C\). Likewise the line segment from \(B\) to \(Y\) is extended to meet \(G_{2}\) at point \(M\) and the segment from \(M\) to \(X\) is extended to meet \(G_{1}\) at point \(D .\) Show that \(A B\) is parallel to \(C D\)

Solution

Draw segment \(B D .\) Now \(\angle B D C=\angle B Y C=\angle L Y M=\angle L X M=\angle A X D=\) \(\angle A B D,\) where the second and the fourth equalities are due to opposite angles and the other three equalities due to angles being in the same arc. Therefore \(A B\) and \(C D\) are parallel.

On Ceva’s theorem

B6b, 2014

A triangle \(C D E\) is given. A point \(A\) is chosen between \(D\) and \(E\) A point \(B\) is chosen between \(C\) and \(E\) so that \(A B\) is parallel to \(C D .\) Let \(F\) denote the point of intersection of segments \(A C\) and \(B D .\) Show that the line joining \(E\) and \(F\) bisects both segments \(A B\) and segment \(C D .\) (Hint: You may use Ceva's theorem. Alternatively, you may additionally assume that the trapezium \(A B C D\) is a cyclic quadrilateral and proceed.)

Solution

By Ceva's theorem in \(\triangle C D E,\) we have \(\frac{D A}{A E} \frac{E B}{B C} \frac{C H}{H D}=1 .\) As \(A B\) and \(C D\) are parallel, \(\frac{D A}{A E}=\frac{B C}{E B}\) so \(C H=D H .\) Also by the basic proportionality theorem, \(\frac{A I}{D H}=\frac{A E}{D E}=\frac{B E}{C E}=\frac{B I}{C H}\) and since \(C H=D H, A I=B I\).

Straight-edge construction

B6c, 2014

Use the results of the previous two problems.

Describe a procedure to do the following task: given two circles \(G_{1}\) and \(G_{2}\) intersecting at two points \(X\) and \(Y\) determine the center of each circle using only a straightedge.

A straightedge is a ruler without any markings. Given two points \(A, B,\) a straightedge allows one to construct the line segment joining \(A, B\). Also, given any two non-parallel segments, we can use a straightedge to find the intersection point of the lines containing the two segments by extending them if necessary.

Solution

Extend \(A D\) and \(B C\) to meet in \(E\) and take \(F=\) the point of intersection of \(A C\) and \(B D .\) By parts (i) and (ii), the line \(E F\) is the bisector of two parallel chords and hence contains a diameter of the circle \(G_{1}\). Repeat the procedure with some other points \(A^{\prime}\) and \(B^{\prime}\) on \(G_{1}\) to get another diameter of \(G_{1}\). The intersection of the two diameters is the center of \(G_{1}\). Repeat the procedure for \(G_{2}\). Note: If lines \(A D\) and \(B C\) do not meet, they are parallel. Then \(A B C D\) must be a rectangle (why?) and its diagonals are diameters, which intersect in the centre of \(G_{1}\). Note that here we have to assume that we can decide if two lines are parallel, which is implicit in the given assumption that if two lines intersect, then we can actually find the point of intersection by extending the given finite segments.

Straight-edge with circle

B6, 2015

You are given the following: a circle, one of its diameters \(A B\) and a point \(X\).

(a) Using only a straight-edge, show in the figure below how to draw a line perpendicular to \(A B\) passing through \(X\). Given two points, a straight-edge can be used to draw the line passing through the given points.

(b) Reconsider your procedure to see if it can be made to work if the point \(X\) is in some other position, e.g., when it is inside the circle or to the "left/right" of the circle. Clearly specify all positions of the point \(X\) for which your procedure in part (a), or a small extension/variation of it, can be used to obtain the perpendicular to \(A B\) through \(X\). Justify your answer.

Solution

(a) Line AX cuts the circle in C. Line BX cuts the circle in D. Lines AD and BC intersect in E. Line XE is perpendicular to line AB. Reason: Angles ADB and ACB are right angles, being angles in a semicircle. The altitudes of triangle \(\mathrm{XAB}\) are concurrent. Two of them are \(\mathrm{AD}\) and \(\mathrm{BC},\) so the third is contained in line XE.

(b) Please refer to the figure shown below. We will do a case-by-case analysis:

Case 2: Suppose X is on one of the two tangents, say the tangent at A,but X is different from A. In this case XA itself is the desired line! In terms of the construction, here we have \(\mathrm{A}=\mathrm{C}=\mathrm{E}\). Of course we have to assume that we can detect whether a line meeting a circle does so in one point or two. But this assumption is implicit in Case 1 also, because there we need to be able to identify the second point of intersection!

Case 3: If \(\mathrm{X}\) is on line \(\mathrm{AB}\), then \(\mathrm{XAB}\) is not a triangle. If \(\mathrm{X}\) is not on line \(\mathrm{AB}\) but \(\mathrm{X}\) is on the circle, then \(\mathrm{XAB}\) is a triangle but \(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{C}=\mathrm{D}=\mathrm{E},\) so we cannot draw line XE. Thus in these cases, the above procedure fails.

An old Russian problem

B12, 2011

In the quadrilateral ABCD shown below, AM and CN are the altitudes of the triangles ABD and CBD, respectively. Show that BN=DM.

Solution

The four points form the vertices of a cyclic quadrilateral with center as O. Drop a perpendicular from O to DB with P as the base. P must bisect DB, so DP=BP.Solution is due to Alexander Bogomolny who discussed this problem on cut-the-knot before it appeared in the CMI paper.