Combinatorics

- Letter arrangement

- Serendipitous sum

- Handshake party

- Sorting with swaps

- Counting students

- Sum of a finite series

- Impossible solid

- Progression of squares

- Pigeon-hole principle

- Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion

- Just count

- Seating boys and girls

- Counting relations

- Count the number of functions

- Count the number of functions II

- Count the number of functions III

- Ordered binary strings

- Number plates

- Count the steps

- Logical puzzle

- Pairwise sums of a set

- Distribute oranges in boxes

- Broken calculator

- First ascent

- Intersection family

- Two-player card game

- Coloring integers

- Difference equations III

- Easy induction

- Smart Induction

- Function on integers

- Function composition

- Combinations with gaps

Letter arrangement

A1, 2011

The word MATHEMATICS consists of 11 letters. The number of distinct ways to rearrange these letters is.

- 11!

- 11!/3

- 11!/6

- 11!/8

Solution

11!/8

Serendipitous sum

B4, 2011

Let S be the set of all 5-digit numbers that contain the digits 1,3,5,7 and 9 exactly once (in usual base 10 representation). Show that the sum of all elements of S is divisible by 11111. Find this sum.

Solution

Each number appears in the \(i\)th place exactly \(4!\) times for \(i\in {1,\ldots,5}\). So the sum of numbers corresponding to each place is

\[ 4!(1+3+5+7+9) = 4!\times 25 = 600 \]

The total sum is therefore:

\[ 10^4\cdot 600 + 10^3\cdot 600 + 10^2\cdot 600 + 10^1\cdot 600 + 600 = 6666600 \]

Handshake party

B1, 2011

In a business meeting, each person shakes hands with each other person once, with the exception of Mr. L.

Since Mr. L arrives after some people have left, he shakes hands only with those present. If the total number of handshakes is exactly \(100,\) how many people left the meeting before Mr. L arrived?

Solution

Let the initial number of people in the party be \(n\). Suppose \(k\) people left the party before Mr. L arrived. The total number of handshakes is then given by:

\[ \binom{n}{2} + (n-k) = 100 \] \[ \binom{n}{2} < 100 < \binom{n+1}{2} \] So \(n=14\) and \(k=5\).

Sorting with swaps

A10, 2022

Let \(P\) denote some arrangement of the numbers \({1,2,\ldots,n}\). A move on \(P\) consists of exchanging the position of element 1 with the position of another element. For example, if \(P=[3,1,4,2]\), then by making one move we can get either \(P=[1,3,4,2]\), \(P=[3,4,1,2]\) or \(P=[3,2,4,1]\). \(P\) is said to be sorted if the numbers are in increasing order. Which of the statements are true?

- The arrangement \([9, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]\) can be sorted in 8 moves and no fewer.

- \( [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 2]\) can be sorted in 8 moves and no fewer.

- \( [1, 3, 4, 2, 9, 5, 6, 7, 8] \) cannot be sorted by any number of moves.

- There exists an arrangement of 99 numbers, i.e. 1 to 99, that cannot be sorted by any number of moves.

Solution

Counting students

A1, 2020

There are \(3\) clubs in a school. A student is a member of at least one of them. \(10\) students are members of all \(3\) clubs. Each club has \(35\) members. Find the minimum and maximum number of students in the school.

Solution

Let us split the students into three categories:

- A-members: Students who belong to one club.

- B-members: Students who belong to two clubs.

- C-members: Students who belong to three clubs.

Each club has 35 slots out of which C-members take up 10 slots. The remaining 25 slots in each club have be to filled with either A or B-members.

Maxima. In order to maximize the number of students we pick only A members. So 75 A-members fill up the remaining slots. The total number of students is then 85.

Minima. There are 75 remaining slots. Each B-student fills up two slots, so there must be at least one A-member. Notice that three B-members can fill up 2 slots of each club. So, 36 B-members can fill up 24 of the remaining slots in each club. The remaining empty slots can be filled up by one B-member and one A-member. So we have 10 C-members, 37 B-members and 1 A-member in all the clubs. In total there are 48 students.

Sum of a finite series

A4, 2019

The sum \( S = 1 + 111 + 11111 + \cdots + \underbrace{11 \cdots 1}_{2k+1} \)

Solution

\begin{align} 9S &= 9 + 999 + 99999 + \cdots + \underbrace{99 \cdots 9}_{2k+1} \\ &= (10-1) + (1000-1) + \cdots + (100^{2k+1}-1) \\ &= \frac{10(100^{k+1} - 1)}{99} - (k+1) \\ S&= \frac{ 10^{2k+3} - 99k - 109}{99\times 9} \end{align}

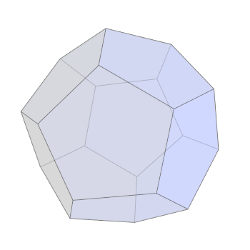

Impossible solid

B6, 2011

Show that there is no solid figure with exactly 11 faces such that each face is a polygon having an odd number of sides.

Solution

Let us add up the number of sides from each face and call this number T. It is given that there are 11 faces and each face has odd sides, so T is odd. However, in any solid each side is counted twice since two faces intersect to form a side. So T must be even, which is a contradiction. Hence such a solid cannot exist.

Progression of squares

A4, 2010

Show that there is no infinite arithmetic progression consisting of distinct integers all of which are squares.

Solution

Suppose the infinite A.P. is given by

\[ a_0^2 < a_1^2 < a_3^2 < \cdots \]

Without loss of generality, assume that \(a_0>0\). Let the common difference be \(d\neq 0\).

The difference between any two consecutive squares in the A.P. is unbounded, hence at some point \( a_i^2 - a_{i-1}^2 > d \).

Another solution due to Th Ravi Singha: Fix an \(n\). Since the common difference is \(d\), the number \(nd\) has finite number of factors. If \(a^2\) and \(b^2\) are pairs of numbers in the sequence that are \(n\) terms apart, then \(a^2 - b^2 = (a+b)(a-b) = nd\). Since RHS has finite number of factors, there can only be finite number of such pairs.

Pigeon-hole principle

A8, 2010

If 8 points in a plane are chosen to lie on or inside a circle of diameter \(2 \mathrm{cm}\) then show that the distance between some two points will be less than \(1 \mathrm{cm}\).

Solution

Divide the disk into six sectors. In each sector only the three corners are mutally at a distance of one from each other. The center of disk is common to all the sectors. Hence, at most 7 points can be kept on the disk that are mutually at a distance 1 from each other.Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion

B3, 2021

You have to form a 7 letter password using 10 digits and 26 letters. Only lower case letters as allowed. For example, 01x01xb, 11bcaa0, etc. are valid passwords.

- How many passwords can you make with 26 letters and 10 digits?

- How many passwords have atleast one alphabet and atleast one digit?

- How many passwords are there with at least one consonant and atleast one vowel and atleast one digit? Note that there are 5 vowels and 21 consonants.

- Suppose there are 12 additional special characters. How many passwords are there with atleast one vowel, one consonant, one digit and one special character?

Solution

- \(36^{7}\).

- \(36^{7} - 26^7 - 10^7 \).

- Let \(V=5,C=21,D=10\) and \(S=12\).

Notation. Let \(P(x_1,\ldots,x_k)\) denote the number \( (x_1+x_2+\ldots+x_k)^7 \) where \( x_i \in \{V,C,D,S\} \).

By principle of inclusion/exclusion the answer is: \[ P(VCD) - \{P(VC)+P(VD)+P(CD)\} + P(V) + P(C) + P(D) \] - \begin{align*} P(VCDS) &- \{ P(VCD) + P(CDS) + P(VCS) + P(VDS) \} \\ &+\{ P(VC)+P(VD)+P(VS)+P(CD)+P(CS)+P(DS)\}\\ &- \{ P(V) + P(C) + P(D) + P(S) \} \end{align*}

Just count

B3, 2010

(a) A computer program prints out all integers from 0 to ten thousand in base 6 using the numerals 0,1,2,3,4 and 5. How many numerals it would have printed?

(b) A 3-digt number \(abc\) in base 6 is equal to the 3-digit number \(cba\) in base 9. Find the digits.

Solution

(a) There are 6 numbers with one digit, \(6^2\) numbers with two digits and so on. We have \(6^5 < 10000 < 6^6\). So there are only \(10000-6^5=2332\) numbers of six digits.

The total numerals the program would have printed is:

\[ 1\times 6 + 2\times 6^2 + 3\times 6^3 + 4\times 6^4 + 5\times 6^5 + 6\times 2332 = 58782 \]

(b) The given condition translates to : \[ c + 6b + 6^2a = a + 9b + 9^2 c \] which means:

\[ 35a - 3b - 80c = 0 \] Since \(a\) is a digit between 1 and 9, \(35a-80c\) is a multiple of 5, so \(b=5\). This means: \[ 35a - 15 = 80c \] The only digits that satisfy are \(a=5\) and \(b=2\). Hence the number is \(552\).

Seating boys and girls

A5, 2013

There are 8 boys and 7 girls in a group. For each of the tasks specified below, write an expression (without simplifying) for the number of ways of doing it.

(a) Sitting in a row so that all boys sit contiguously and all girls sit contiguously, i.e., no girl sits between any two boys and no boy sits between any two girls.

(b) Sitting in a row so that between any two boys there is a girl and between any two girls there is a boy

(c) Choosing a team of six people from the group

(d) Choosing a team of six people consisting of unequal number of boys and girls

Solution

(a) \(2 \times 8 ! \times 7 !\) (The factor of 2 arises because the two blocks of boys and girls can switch positions.)

(b) \(8 ! \times 7 !\) (There is no factor of 2 because there must be a boy at each end.)

(c) \(\left(\begin{array}{c}15 \\ 6\end{array}\right)\)

(d) \(\left(\begin{array}{c}15 \\ 6\end{array}\right)-\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 3\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 3\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 6\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 5\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 1\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 4\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 2\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 2\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 4\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l}8 \\ 1\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 5\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l}7 \\ 6\end{array}\right)\)

Counting relations

B6, 2020

6 (i) Find the total number of anti-symmetric relations \(R\) from \(S \times S\) where \(S=\{1,2,3\cdots n\}.\) An anti-symmetric relation is defined as: \((a,b)\in R\implies (b,a)\notin R.\)

Solution

From the definition it follows that \( (a,a) \notin R \). For any unordered pair \( \{a,b\} \) there are three possibilities:

- \( (a,b) \in R \)

- \( (b,a) \in R \)

- \( (a,b) \notin R \)

6. (ii) We have a set of points on a 2D-plane. Let \(S\) be a set of \(k\) vertical points and \(T\) be a set of \(n\) vertical points as shown below. The \(i\)th point in \(S\) (resp. \(T\)) is denoted by \(S_i\) (resp. \(T_i\)).

An edge is an ordered pair \( \left(x,y\right) \) with \(x \in S\) and \(y \in T\). A set of edges is said to be an arrangement if the following holds:

- Any pair of edges in the arrangement is non-crossing, that is, if \( (S_a,T_b) \) and \( (S_c,T_d) \) are edges, then \(a\geq c \Leftrightarrow b\geq d\).

- Every point in \(S\) and \(T\) is present in some edge in the arrangement.

Let \(f(k,n)\) denote the total number of arrangements. Write a recurrence for \( f(k,n) \). The expression in the recurrence must have fixed number of terms.

Solution

In any arrangement, \( (S_k,T_n) \) is an edge. Let us partition the arrangements into three types:- Type I: \( (S_{k}, T_{n-1}) \) is an edge. There are \(f(k,n-1)\) such arrangements.

- Type II: Both \( (S_{k}, T_{n-1}) \) and \( (S_{k-1},T_{n}) \) are not edges. There are \(f(k-1,n-1)\) such arrangements.

- Type III: \( (S_{k-1}, T_{n}) \) is an edge. There are \(f(k-1,n-1)\) such arrangements.

For the base cases, both \( f(1,n)=1 \) and \( f(k,1)=1 \). For, \(n,k>1\), recurrence is given by: \[ f(k,n) = f(k,n-1) + f(k-1,n-1) + f(k-1,n) \]

6. (iii) Find formulas for \( f(2,n) \) and \( f(3,n) \).

Solution

Notice that \(f(2,2)=3\). Using the recurrence in part (ii): \begin{align} f(2,n) &= f(2,n-1) + f(1,n-1) + f(1,n) \\ &= f(2,n-1) + 2 \\ &= f(2,2) + 2(n-2) \\ &= 2n-1 \end{align} \begin{align} f(3,n) &= f(3,n-1) + f(2,n-1) + f(2,n) \\ &= f(3,n-1) + 2n-3 + 2n-1\\ &= f(3,n-1) + 4(n-1) \\ &= f(3,n-1) + 4(n-1) \\ &= f(3,n-2) + 4[ (n-2) + (n-1)] \\ &\;\; \vdots \\ &= f(3,1) + 4\cdot \frac{n(n-1)}{2} \\ &= 2n^2-2n+1 \end{align}

Count the number of functions

B3, 2014

6 (i) How many functions are there from the set \(\{1, \ldots, k\}\) to the set \(\{1, \ldots, n\} ?\)

6 (ii) Let \(P_{k}\) denote the set of all subsets of \(\{1, \ldots, k\} .\) Find a formula for the number of functions \(f\) from \(P_{k}\) to \(\{1, \ldots, n\}\) such that \(f(A \cup B)=\) the larger of the two integers \(f(A)\) and \(f(B)\).

Verify using your formula that that for \(k=3\) and \(n=4\) there are 100 such functions.

Example: When \(k=2,\) the set \(P_{2}\) contains 4 elements: the empty set \(\phi,\{1\},\{2\}\) and \(\{1,2\} .\)

The function \(f\) given by \(\phi \rightarrow 2,\{1\} \rightarrow 3,\{2\} \rightarrow 4,\{1,2\} \rightarrow 4\) satisfies the given condition. But the function \(g\) given by \(\phi \rightarrow 2,\{1\} \rightarrow 3,\{2\} \rightarrow 4,\{1,2\} \rightarrow 5\) does not, because \(g(\{1\} \cup\{2\})=g(\{1,2\})=5 \neq\) the larger of \(g(\{1\})\) and \(g(\{2\})=\max (3,4)=4\)

Solution

(i) As there are \(n\) choices each for the values of \(f(1), \ldots, f(k)\) and as all these choices are independent of each other, the number of functions is \(n^{k}\).

(ii) Note that \(f(A)=\max \{f(\{j\}) \mid j \in A\}\), so the function \(f\) is completely decided by its values on the empty set \(\phi\) and on the one element subsets \(\{1\},\{2\}, \ldots,\{k\} .\) If \(f(\phi)=i,\) then each of \(f(\{1\}), f(\{2\}), \ldots, f(\{k\})\) can be chosen to be any of the numbers \(i, i+1, \ldots, n\) Thus there are \(k\) independent choices for each of which there are \(n-i+1\) options. So the number of desired functions for which \(f(\phi)=i\) is \((n-i+1)^{k} .\) Now we sum over all values of \(i=1,2, \ldots, n\) to get the total number to be \(1^{k}+2^{k}+\cdots+n^{k} .\) (When \(k=3\) and \(n=4\) we get \(1^{3}+2^{3}+3^{3}+4^{3}=100,\) as mentioned in the problem.)

Count the number of functions II

B1, 2019

Let \(\operatorname{Map}(n)\) be the set of all functions \(f:\{1,2, \ldots, n\} \rightarrow\) \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\}\). For \(f, g \in \operatorname{Map}(n), f \circ g\) denotes the function in \(\operatorname{Map}(n)\) that sends \(x\) to \(f(g(x))\)

(a) Let \(f \in \operatorname{Map}(n) .\) If for all \(x \in\{1, \ldots, n\}\), \(f(x) \neq x\), show that \(f \circ f \neq f\)

(b) Count the number of functions \(f \in \operatorname{Map}(n)\) such that \(f \circ f=f\)

Solution

(a) Let \(f(f(x))=f(x)\) and substitute \(y=f(x)\). Then we get \(f(y)=y\), a contradiction.

(b) The above implies that each \(x\) has to map to a fixed point of \(f\), that is, a \(y\) such that \(f(y)=y\). So in order to count the number of such functions we first need to decide the number of fixed points. The number functions that have exactly \(k\) fixed points is \(\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ k\end{array}\right) k^{n-k}\). In order to get the total number, sum the previous quantity over \(1 \leq k \leq n\).

Count the number of functions III

A8, 2022

Let \(N=\{1,2,\ldots,9\}\) and \(L=\{a,b,c\}\).

- \(L \cup N\) is arranged on a line with the letters appearing consecutively (in any order). The number of such arrangements are less than \(10!\times 5\).

- More than half of the functions from \(N\) to \(L\) have \(b\) in their range.

- The number of one-to-one functions from \(L\) to \(N\) is less than 512.

- The number of functions \(N\) to \(L\) that do not map consecutive numbers to consecutive letters is greater than 512.

Solution

Ordered binary strings

A2, 2015

Consider all finite letter-strings formed by using only two letters A and B. We consider the usual dictionary order on these strings. For example, ABAA < ABB and AB < ABAA.

For each of the statements below, state if it is true or false.

(a) Let \(w\) be an arbitrary string. There exists a unique string \(y\) satisfying both the following properties:

(i) \(w < y\) and

(ii) there is no string \(x\) with \(w < x < y\)

(b) It is possible to give an infinite decreasing sequence of strings, i.e. a sequence \(w_{1}, w_{2}, \ldots,\) such that \(w_{i+1}< w_{i}\) for each positive integer \(i\)

(c) Fewer than 50 strings are smaller than ABBABABB

Solution

True. Append A to \(w\).

True. B, AB, AAB, AAAB, ...

False. There are infinitely many such strings e.g. A, AA, AAA, AAAA,

Number plates

A8, 2015

The format for car license plates in a small country is two digits followed by three vowels, e.g. \(04\) IOU. A license plate is called "confusing" if the digit 0 (zero) and the vowel O are both present on it. For example \(04 ~ I O U\) is confusing but \(20 \mathrm{AEI}\) is not. (i) How many distinct number plates are possible in all? (ii) How many of these are not confusing?

Solution

(i) \(10^{2} \times 5^{3}=12500\).

(ii) \(10^{2} \times 4^{3}\) plates without vowel \(\mathrm{O}+9^{2} \times\left(5^{3}-4^{3}\right)\) plates with vowel O but without 0. This gives \(6400+4941=11341\).

Count the steps

A4, 2016

A step starting at a point \(P\) in the \(X Y\) -plane consists of moving by one unit from \(P\) in one of three directions: directly to the right or in the direction of one of the two rays that make the angle of \(\pm 120^{\circ}\) with positive \(X\) -axis.

A path consists of a number of such steps, each new step starting where the previous step ended. Points and steps in a path may repeat.

Find the number of paths starting at (1,0) and ending at (2,0) that consist of

(i) exactly 6 steps

(ii) exactly 7 steps.

Solution

(i) Let there be \(a\) steps to the right (east), b steps north-west and c steps southwest. The total number of steps is \(a+b+c .\) The key idea is to think of the northwest step as a move in the complex plane along \(\omega,\) the complex cube root of unity, the southwest step as a move in the complex plane along \(\omega^{2}\) and the step to the right as a move along \(\omega^{3}=1\) From the hypothesis we then have \(a+b \omega+c \omega^{2}=1 .\) Using \(1+\omega+\omega^{2}=0\) we see that \(a-1=b=c .\) This then rules out \(a+b+c=6,\) so the number of 6 step paths is zero.

(ii) A 7 step path is possible only with \(a=3, b=2, c=2\). The number of such paths is the multinomial coefficient \(\left(\begin{array}{c}7 \\ 3,2,2\end{array}\right)=210\).

Logical puzzle

A1, 2016

Four children K, L, M and R are about to run a race. They make some predictions as follows. K says: M will win. Myself will come second. R says: M will come second. L will be third. M says: L will be last. R will be second. After the race, it turns out that each person has made exactly one correct and one incorrect prediction. Write the result of the race in the order from first to the last.

Solution

If K comes second, then L was third (one correct answer for R). But then R would also need to be second (one correct answer for M, a contradiction. So K cannot be second. So M must have won, etc. The order is M R L K.

Pairwise sums of a set

B4, 2016

Let \(A\) be a non-empty finite sequence of \(n\) distinct integers \(a_{1}< a_{2}< \cdots< a_{n} .\) Define \[ A+A=\left\{a_{i}+a_{j} \mid 1 \leq i, j \leq n\right\} \] i.e., the set of all pairwise sums of numbers from \(A\). E.g., for \(A=\{1,4\}, A+A=\{2,5,8\}\).

(a) Show that \(|A+A| \geq 2 n-1 .\) Here \(|A+A|\) means the number of elements in \(A+A\).

(b) Prove that \(|A+A|=2 n-1\) if and only if the sequence \(A\) is an arithmetic progression.

(c) Find a sequence \(A\) of the form \(0<1 < a_{3} < \cdots < a_{10}\) such that \(|A+A|=20\).

Solution

(a) The following \(2 n-1\) numbers in \(A+A\) are distinct: \(a_{1}+a_{1}< a_{1}+a_{2}<\cdots< a_{1}+a_{n}< a_{2}+a_{n}< \ldots< a_{n}+a_{n}\).

A way to visualize is to write \(a_{i}+a_{j}\) at point \((i, j)\) in the XY-plane. Any step to the right or up increases the number. To reach from \(2 a_{1}\) to \(2 a_{n}\) needs \(2 n-1\) such steps. The given example is the path along bottom row and then rightmost column.

(b) Suppose the \(a_{i}\) form an arithmetic progression. Then for a fixed \(k\), the value of \(a_{i}+a_{k-i}\) is constant for all possible \(i,\) where \(2 \leq k \leq 2 n\). For the converse, we use induction.

There is nothing to prove for \(n=1,2\).

For \(n>2,\) remove \(a_{n}\) from \(A\) to get a set \(B .\) Now \(|A+A|-|B+B| \geq 2,\) because the two distinct numbers \(a_{n-1}+a_{n}\) and \(2 a_{n}\) in \(A+A\) are greater than all numbers in \(B+B\).

So for \(|A+A|=2 n-1\) to happen, one must have \(|B+B|=2 n-3,\) which by induction forces \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n-1}\) to be in an arithmetic progression. Moreover \(a_{n-2}+a_{n}\) must be in \(B+B\) and it can only be the largest number \(2 a_{n-1}\) (because all others are smaller than \(a_{n-2}+a_{n}\) ). This shows that \(a_{n}\) is the next term of the same arithmetic progression.

(c) \(0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10.\)

Can you prove that the answer is unique?

Distribute oranges in boxes

A2, 2017

10 oranges are to be placed in 5 distinct boxes labeled \(\mathrm{U}, \mathrm{V}, \mathrm{W}, \mathrm{X}, \mathrm{Y} .\) A box may contain any number of oranges including no oranges or all the oranges. What is the number of ways to distribute the oranges so that exactly two of the boxes contain exactly two oranges each?

Solution

From the five distinct boxes, there are 10 ways to pick the two boxes that will have 2 oranges each. We need to distribute the remaining 6 oranges in the remaining three boxes such that none of the three boxes gets exactly 2 oranges. The possible distributions are \(6+0+0\) (which can be done in 3 ways) or \(5+1+0\) (6 ways) or \(4+1+1\) (3 ways) or \(3+3+0(3\) ways \() .\) Thus the required answer is \(10 \times(3+6+3+3)=150\)

Broken calculator

A7, 2019

A broken calculator has all its 10 digit keys and two operation keys intact. Let us call these operation keys A and B. When the calculator displays a number \(n\) pressing A changes the display to \(n+1\). When the calculator displays a number \(n\) pressing \(B\) changes the display to \(2 n .\) For example, if the number 3 is displayed then the key strokes ABBA changes the display in the following steps \(3 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 16 \rightarrow 17\).

If 1 is on the display what is the least number of key strokes needed to get 260 on the display?

Solution

\(9,\) there are exactly two sequences, for example, \(BBBBBBABB\).

First ascent

A8, 2019

Let \(\pi=\pi_{1} \pi_{2} \ldots \ldots \pi_{n}\) be a permutation of the numbers \(1,2,3, \ldots, n\).

We say \(\pi\) has its first ascent at position \(k<n\) if \(\pi_{1}>\pi_{2} \ldots>\pi_{k}\) and \(\pi_{k}<\pi_{k+1}\).

If \(\pi_{1}>\pi_{2}>\ldots>\) \(\pi_{n-1}>\pi_{n}\) we say \(\pi\) has its first ascent in position \(n\).

For example when \(n=4\) the permutation 2134 of has its first ascent at position 2 The number of permutations which have their first ascent at position \(k\) is ...

Solution

\(\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ k\end{array}\right)(n-k) !-\left(\begin{array}{c}n \\ k+1\end{array}\right)(n-k-1) !\)

Intersection family

B3, 2012

(a) We want to choose subsets \(A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{k}\) of \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\}\) such that any two of the chosen subsets have nonempty intersection. Show that the size \(k\) of any such collection of subsets is at most \(2^{n-1}\)

(b) For \(n>2\) show that we can always find a collection of \(2^{n-1}\) subsets \(A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots\) of \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\}\) such that any two of the \(A_{i}\) intersect, but the intersection of all \(A_{i}\) is empty.

Solution

(a) If a set \(A\) is in such a collection \(\mathcal{C},\) then the complement of \(A\) cannot be in \(\mathcal{C}\).

Therefore \(|\mathcal{C}| \leq \frac{1}{2}(\) total number of subsets of \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\})=\frac{1}{2} 2^{n}=2^{n-1}\)

(b) Solution 1. Take all \(2^{n-1}\) subsets of \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\}\) containing \(1\), remove the singleton set \(\{1\}\) and instead include its complement.

(b) Solution 2. For \(n=3,\) the four sets \(\{1,2\},\{2,3\},\{1,3\},\{1,2,3\}\) give a unique solution. For \(n>3\) take the union of each of these 4 sets with all \(2^{n-3}\) subsets of \(\{4, \ldots, n\}\).

Two-player card game

B6, 2021

You and your friend are playing a game where there are 2 stacks of cards:

Stack A has \(n\) cards and each card has a number from the set \( \{1,2,...,m\} \).

Stack B has \(m\) cards and each card has a number from the set \( \{1,2,...,n\} \).

You start with \(t_0=0\) and note down the following sequence \(t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots\). The game proceeds in steps as follows:

If \(t_j \leq 0\), pick out the topmost card from stack A and set \[t_{j+1}=t_j + \text{number on the topmost card drawn from Stack A}\] If \(t_j> 0\), pick out the topmost card from stack B and set \[t_{j+1}=t_j - \text{number on the topmost card drawn from stack B}\] The game ends when a player has to draw a card from an empty stack.

Prove that

- \(1-n \leq t_j \leq m \) for all \(j\)

- There exists distinct indices \(i\) and \(j\) such that \(t_i=t_j\)

- Prove that there exists a non empty subset in stack A and another in B such that the sum of the numbers on those cards are equal.

Solution

- If \(t_j\leq 0\), a card from A is removed. The maximum value of a card in A is \(m\) so \(t_j\) can at most be \(m\). Similarly, a card from B is subtracted when the value of \(t_j \geq 1\). Hence, the smallest value it can take is \(1-n\).

- From (1) we see that the \(t\)-sequence can take at most \(n\) distinct non-positive values and at most \(m\) distinct positive values. We consider two ways in which the game can end:

Case 1: Cards in stack B are empty.

Suppose the game ended after using up \(m\) cards from B and \(p\leq n\) cards from A. Since the game has ended the value of \(t_{m+p}\) must be positive. In addition, the value of \(t\) before every card in B was added must have been positive (by the game's rule). So the sequence \(t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots,t_{m+p}\) contains \(m+1\) positive numbers. But since the sequence contains \(m\) distinct positive numbers, two \(t\)s must have the same value by pigeon-hole principle.

Case 2: Cards in stack A are empty.

We use a similar argument. Suppose the game ended after using up \(n\) cards from A and \(p\leq n\) cards from B. Since the game has ended the value of \(t_{n+p}\) must be non-positive. In addition, the value of \(t\) before every card in A was added must have been non-positive. So the sequence \(t_0,t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots,t_{m+p}\) contains \(n+1\) non-positive numbers. But since the sequence contains \(n\) distinct non-positive numbers, two \(t\)s must have the same value by pigeon-hole principle. - From (2), some \(t_i=t_j\). The sequence of cards added between \(t_i\) and \(t_j\) sums to zero. So some proper subset of \(A\) and \(B\) have equal sums.

Coloring integers

B5, 2017

Each integer is colored with exactly one of three possible colors - black, red or white satisfying the following two rules:

Rule 1: The negative of a black number must be colored white.

Rule 2: The sum of two white numbers (not necessarily distinct) must be colored black.

(a) Show that the negative of a white number must be colored black.

(b) Show that the sum of two black numbers must be colored white.

(c) Determine all possible colorings of the integers that satisfy these rules.

Solution (a)

(a) Suppose an integer \(n\) is colored white. Then \((n+n)=2 n\) is black, so \(-2 n\) is white, so \(-2 n+n=-n\) is black. Thus, the negative of a white number must be colored black.

Solution (b)

(b) Now suppose the integers \(n\) and \(m\) are both colored black. Then \(-n\) and \(-m\) are both white, so \(-n-m\) is back, so \(n+m\) is white. Thus, the sum of two black numbers must be colored white.

Solution (c)

(c) One possible coloring has all the integers colored red, since there are no conditions on red numbers. If that is not the case, let \(n\) be the smallest positive integer that is not colored red. Suppose the number \(n\) is colored black. Then we claim the remaining colors are all fully determined. Namely, the numbers of the form \((3 k+1) n\) will be black, the numbers of the form \((3k+2) n\) will be white, and the numbers of the form \((3k)n\) will be red, for all integers \(k\). And all remaining colors will be red. On the other hand, if the number \(n\) is colored white to begin with, then the remaining numbers will be determined by the same rules, but with black and white switched.

Thus we have listed all possible colorings. In order to prove the above claim, we first prove one more rule the colors must obey. Namely, that

Lemma. The sum of a black number and a white number must be colored red.

Proof. Suppose \(n\) is black and \(m\) is white, and that \(n+m\) is black. But then \((n+m)+(-m)\) is the sum of two black numbers, and must be colored white, which is a contradiction. Similarly, the sum of \(n\) and \(m\) cannot be white. Therefore it must be red.\(\:\square \)

Using this rule, we deduce that the numbers of the form \((3k+1)n\) will be black, the numbers of the form \((3k+2) n\) will be white, and the numbers of the form \((3k)n\) will be red, for all integers \(k\).

Lemma. All the numbers that are not multiples of \(n\) are colored red.

We can prove this by contradiction. As before \(n\) is the smallest positive integer that is not red, and it is colored black. Suppose \(m\) is the smallest positive integer that is neither red nor a multiple of \(n\).

Then \(m=qn+r\), where \(0 < r< n\) is the remainder when \(m\) is divided by \(n\).

We know this remainder is nonzero, since \(m\) is not a multiple of \(n .\) We also know that \(q > 0,\) since \(m > n\). Suppose \(m\) is white. Then, because \(-n\) is white, we know \(m-n=(q-1) n+r\) is black, which gives us a smaller non-red positive integer that is not a multiple of \(n\). On the other hand, suppose \(m\) is colored black. Then \(-2 n\) is black, so \(m-2 n=(q-2) n+r\) is white. If \(q<1,\) this gives us a smaller positive non-red integer that \(^{\prime}\) s not a multiple of \(n_{1}\) which is a contradiction, provided \(q>1 .\) But if \(q=1,\) and \(m-2 n=-n+r\) is white, that means that \(n-r\) is black, a contradiction. \(\:\square\)

Difference equations III

B6, 2013

Define \(f_{k}(n)\) to be the sum of all possible products of \(k\) distinct integers chosen from the set \(\{1,2, \ldots, n\},\) i.e.,

\[ f_{k}(n)=\sum_{1 \leq i_{1}<i_{2}<\ldots<i_{k} \leq n} i_{1} i_{2} \ldots i_{k} \]

(a) For \(k>1,\) write a recursive formula for the function \(f_{k},\) i.e., a formula for \(f_{k}(n)\) in terms of \(f_{\ell}(m),\) where \(\ell<k\) or \((\ell=k\) and \(m<n)\)

(b) Show that \(f_{k}(n),\) as a function of \(n,\) is a polynomial of degree \(2k\).

(c) Express \(f_{2}(n)\) as a polynomial in variable \(n\).

Solution (a)

(a) Break up the terms in the definition of \(f_{k}(n)\) into two groups: the terms in which \(i_{k}=n\) add up to \(n f_{k-1}(n-1)\) and the remaining terms, i.e., the ones in which \(i_{k} \leq n-1,\) add up to \(f_{k}(n-1) .\) So we get \(f_{k}(n)=n f_{k-1}(n-1)+f_{k}(n-1)\)

Solution (b)

(b) We prove the statement by induction on \(k .\) First \(f_{1}(n)=\sum_{i=1}^{n} i=\frac{n(n+1)}{2},\) a polynomial of degree 2 as desired. For \(k>1,\) we have by part a the equation \(f_{k}(n)-f_{k}(n-1)=\) \(n f_{k-1}(n-1) .\) The right hand side is a polynomial of degree \(1+2(k-1)=2 k-1,\) where \(2(k-1)\) is the degree of \(f_{k-1}(n-1)\) by induction and the added 1 comes from the factor n. since successive differences in the values of \(f_{k}\) are given by a polynomial of degree \(2 k-1,\) the function \(f_{k}\) on positive integers is given by a polynomial of degree 1 more, i.e., of degree \(2 k\) Note: The previous statement is a standard fact, which can be explained as follows. If we assume that \(f_{k}(n)\) is a polynomial, then its degree is easily found, because for any polynomial \(f\) of degree \(m,\) its "successive difference" function \(f(x)-f(x-1)\) is a polynomial of degree \(m-1 .\) (Reason: If the leading term of \(f(x)\) is \(a x^{m},\) then the leading term in \(f(x)-f(x-1)\) is \(a m x^{m-1},\) as seen by expanding the power of \(x-1\) in \(a x^{m}-a(x-1)^{m}\) The remaining terms in \(f(x)-f(x-1)\) do not matter because by expanding powers of \(x-1\) in them and simplifying, we only get monomials of degree \(< m-1 .)\) (2) In fact, based on the difference equation, \(f_{k}(n)\) must be a polynomial in the variable \(n .\) This is a consequence of the following well-known fact.

Solution (c)

c) By part a we have \(f_{2}(n)-f_{2}(n-1)=n f_{1}(n-1)=n \times \frac{n(n-1)}{2}=\frac{1}{2}\left(n^{3}-n^{2}\right)\). Similarly \(f_{2}(n-1)-f_{2}(n-2)=\frac{1}{2}\left((n-1)^{3}-(n-1)^{2}\right)\) and so on up to \(f_{2}(2)-f_{2}(1)=\frac{1}{2}\left(2^{3}-2^{2}\right)\) Note that \(f_{2}(1)=0,\) which we may also write as \(\frac{1}{2}\left(1^{3}-1^{2}\right) .\) Adding up, we get for any \(n \geq 1, f_{2}(n)=\sum_{j=1}^{j=n} \frac{1}{2}\left(j^{3}-j^{2}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{n^{2}(n+1)^{2}}{4}-\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6}\right),\) where we have used standard formulas for the sum of first \(n\) cubes and of first \(n\) squares.

Claim. Given a polynomial \(h(x)\) of degree \(d\), there is a polynomial \(g(x)\) of degree \(d+1\) such that \(g(x)-g(x-1)=h(x)\).

Proof: Induction on \(d,\) the degree of \(h .\) If \(h(x)=c\) a constant, then \(g(x)=c x\) works. Now for \(d>1,\) it is enough to find a polynomial \(g(x)\) such that \(g(x)-g(x-1)=x^{d}\) (because if \(h(x)=c x^{d}+\tilde{h}(x),\) where \(\tilde{h}\) has degree \(< d\), by induction we find \(\tilde{g}\) for \(h\) and then \(c g(x)+\tilde{g}(x)\) works for \(h(x)) .\) To find such \(g(x)\), notice that for \(g_{1}(x)=x^{d+1},\) we have \(h_{1}(x)=g_{1}(x)-g_{1}(x-1)=(d+1) x^{d}+h_{2}(x),\) where \(h_{2}(x)\) is a polynomial of degree \(d-1 .\) By induction \(h_{2}(x)=g_{2}(x)-g_{2}(x-1)\) for a polynomial \(g_{2}(x)\) of degree \(d .\) Now \(g(x)=\frac{1}{d+1}\left(g_{1}(x)-g_{2}(x)\right)\) works. \(\:\square\).

Easy induction

A6, 2010

Prove that \[ \frac{2}{0 !+1 !+2 !}+\frac{3}{1 !+2 !+3 !}+\cdots+\frac{n}{(n-2) !+(n-1) !+n !}=1-\frac{1}{n !} \]

Solution 1

Let \(P(n)\) denote LHS.

Base case \(n=2\).

\(\frac{2}{0 !+1 !+2 !}=1-\frac{1}{2 !} \quad\) hence \(P(2)\) is true.

Inductive step: Assume \(P(n)\) to be true.

\begin{align} P(n+1) &=P(n)+\frac{n+1 !}{n-1 !+n !+n+1 !} \\ &=1+\left(\frac{n+1}{n-1 !+n !+n+1 !}-\frac{1}{n !}\right) \\ &=1+\frac{1}{(n+1) !}\left[\frac{(n+1)}{\left[\frac{1}{n(n+1)}+\frac{1}{n+1}+1\right]}-(n+1)\right]\\ &= 1+\frac{1}{(n+1) !}\left[\frac{(n+1) \cdot n \cdot(n+1)}{1+n+n(n+1)}-(n+1)\right] \\ &= 1+\frac{1}{(n+1) !}[n-(n+1)] \\ &=1-\frac{1}{(n+1)!} \end{align}

Hence \(P(n+1) \quad\) holds.

Solution 2

Note that \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{k+2}{k !+(k+1) !+(k+2) !} &=\frac{k+2}{k ![1+k+1+(k+1)(k+2)]} \\ &=\frac{1}{k !(k+2)} \\ &=\frac{k+1}{(k+2) !} \\ &=\frac{(k+2)-1}{(k+2) !} \\ &=\frac{1}{(k+1) !}-\frac{1}{(k+2) !} \end{aligned} \]

Telescoping the sum gives the desired value.

Reference: Problem 13. 101 Problems in Algebra. Titu Andreescu and Zuming Feng.

Smart Induction

B1a, 2018

A natural number \(k\) is called stable if there exist \(k\) distinct natural numbers \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k},\) each \(a_{i}>1,\) such that \[ \frac{1}{a_{1}}+\cdots+\frac{1}{a_{k}}=1 \]

Show that if \(k\) is stable then \(k+1\) is also stable. find all the stable numbers.

Solution

Verify that 1 and 2 are not stable. Number 3 is stable since:

\[ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{6} = 1 \]

Number 4 is also stable since:\[ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{6} \right) = 1 \]

This gives the general idea. If \(k \geq 3\) is stable, then there are \(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}\) all distinct and \(\sum \frac{1}{a_{i}}=1 .\) This implies that \(\frac{1}{2}+\sum \frac{1}{2 a_{i}}=1 .\) Hence all numbers except 1 and 2 are stable.

Reference. Egyptian fractions.

Function on integers

B3, 2018

Let \(f\) be a function on the nonnegative integers defined as:

\[ f(2 n)=f(f(n)) \quad \text { and } \quad f(2 n+1)=f(2 n)+1 \]

(a) If \(f(0)=0,\) find \(f(n)\) for every \(n\).

(b) Show that \(f(0)\) cannot equal 1.

(c) For what nonnegative integers \(k\) (if any) can \(f(0)\) equal \(2^{k}\)?

Solution

(a) Suppose \(f(0)=0\) then \(f(1)=1\) and \(f(2)=f(f(1))=f(1)=1\). It implies that \(f(3)=1+1=2\) and \(f(4)=f(1)=1\). The pattern continues and we get that if \(2 k+1 \geq 3\) then \(f(2 k+1)=2 .\) On the other hand if \(2 k \geq 4\) then \(f(2 k)=1\)

(b) Suppose \(f(0)=1 .\) We have \(f(0)=f(2 \cdot 0)=f(f(0))=f(1)\). But we also have \(f(1)=f(0)+1,\) a contradiction.

(c) Suppose \(f(0)=2^{k} .\) Then, \(2^{k}=f(2 \cdot 0)=f(f(0))=f\left(2^{k}\right),\) and \(f\left(2^{k}+1\right)=f\left(2^{k}\right)+\) \(1=2^{k}+1 .\) Notice that \(f(1)=f(0)+1=2^{k}+1,\) and \(f(2)=f(f(1))=2^{k}+1\)

In this way, we see that for any \(n, f\left(2^{n}\right)=2^{k}+1 .\) This contradicts the fact that \(f\left(2^{k}\right)=2^{k}\)

Function composition

B9, 2012

Let \(N\) be the set of non-negative integers. Suppose \(f: N \rightarrow N\) is a function such that \(f(f(f(n)))<f(n+1)\) for every \(n \in N .\) Prove that \(f(n)=n\) for all \(n\) using the following steps.

a) If \(f(n)=0,\) then \(n=0\)

Solution (a)

Let \(f(n)=0 .\) If \(n>0,\) then \(n-1\) is in the domain of \(f\) and \(f(f(f(n-1)))< f(n)=0\) which is a contradiction, since 0 is the smallest possible value of \(f .\)

b) If \(f(x)< n\), then \(x< n\).

Solution (b)

We use induction on \(n\).

If \(n=1,\) then this is just part a. Assuming the statement up to \(n\) we need to prove that if \(f(x)< n+1,\) then \(x< n+1 \). If \(f(x)< n,\) then by induction \(x< n,\) so \(x< n+1 \). So let \(f(x)=n \). If \(x=0,\) we are done. Otherwise \(f(f(f(x-1)))< f(x)=n\) and by using induction thrice we get in succession \(f(f(x-1))< n,\) then \(f(x-1)< n\) and then \(x-1< n,\) i.e., \(x< n+1\) as desired.

c) \(f(n)< f(n+1)\) and \(n< f(n+1)\) for all \(n\)

Solution (c)

Apply part b to \(f(f(f(m)))< f(m+1)\) (with \(x=f(f(m))\) and \(n=f(m+1))\) to get

\(f(f(m))< f(m+1) .\) Apply part \(b\) to this with \(x=f(m)\) and \(n=f(m+1)\) to get \(f(m)< f(m+1) .\) Again apply part b to get \(m< f(m+1)\)

d) \(f(n)=n\) for all \(n\)

Solution (d)

By part c, \(f\) is increasing and \(f(n) \geq n .\) If \(f(n)>n,\) then \(f(f(n))>f(n)\) (since \(f\) is increasing) and so \(f(f(n))>n,\) i.e., \(f(f(n)) \geq n+1 .\) Again, since \(f\) is increasing, \(f(f(f(n))) \geq f(n+1),\) a contradiction.

Combinations with gaps

B5, 2018

An ancient alphabet has \(n\) letters \(b_{1}, \ldots, b_{n} .\) For some \(k< n / 2\) assume that all words formed by any of the \(k\) letters , written from left to right, are present in the vocabulary. These words are called \(k\)-words. Such a \(k\)-word is considered sacred if:

i) no letter appears twice and,

ii) if a letter \(b_{i}\) appears in the word then the letters \(b_{i-1}\) and \(b_{i+1}\) do not appear. (Here \(b_{n+1}=b_{1}\) and \(\left.b_{0}=b_{n} .\right)\)

For example, if \(n=7\) and \(k=3\) then \(b_{1} b_{3} b_{6}, b_{3} b_{1} b_{6}, b_{2} b_{4} b_{6}\) are sacred 3-words. On the other hand, the words \(b_{1} b_{7} b_{4}, b_{2} b_{2} b_{6}\) are not sacred.

(a) How many sacred \(k\)-words are there?

(b) Calculate the number of 4-words for \(n=10\).

Solution

(a) We will count the sacred words starting with \(b_{1}\). since \(b_{1}\) is chosen \(b_{n}\) and \(b_{2}\) are out of the picture. In order to fill the remaining \(k-1\) positions we have to choose non-consecutive \(b_{i}\)s. Note that, specifying these \(b_{i}\)s is same as specifying the gaps between them. For example, let \(n=7, k=3\) and we would like to choose \(b_{1}, b_{3}, b_{6}\).

Then the triple (1,2,1) specifies that leave one alphabet after \(b_{1},\) drop two aft er \(b_{3}\) and drop one aft er \(b_{6}\).

Hence, in general let \(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{k}\) be these gaps.

It is clear that each of this gap is at least 1 and they add up to \(n-k\).

So our counting problem can be reformulated as: "In how many different ways can we choose \(k\) natural numbers, each of which is at least \(1,\) that add up to \(n-k\)?"

The answer is \(\left(\begin{array}{c}n-k-1 \\ k-1\end{array}\right)\).

However, we have not assigned positions to these letters yet. This can be done in \((k-1) !\) ways. Hence the number of ways is

\[ (k-1) !\left(\begin{array}{c} n-k-1 \\ k-1 \end{array}\right) \]

In order to count the total number of sacred words we just need to multiply the above number by \(n .\) The final answer is

\[n(k-1) !\left(\begin{array}{c}n-k-1 \\ k-1\end{array}\right)\]

(b) For \(n=10\) and \(k=4\) the above count is \(\displaystyle 10\times 3! \times \binom{5}{3} = 600 \).

--- ### Two-player card game {: .d-inline-block} B6, 2021 {: .label} You and your friend are playing a game where there are 2 stacks of cards:

Stack A has \(n\) cards and each card has a number from the set \( \{1,2,...,m\} \).

Stack B has \(m\) cards and each card has a number from the set \( \{1,2,...,n\} \).

You start with \(t_0=0\) and note down the following sequence \(t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots\). The game proceeds in steps as follows:

If \(t_j \leq 0\), pick out the topmost card from stack A and set \[t_{j+1}=t_j + \text{number on the topmost card drawn from Stack A}\] If \(t_j> 0\), pick out the topmost card from stack B and set \[t_{j+1}=t_j - \text{number on the topmost card drawn from stack B}\] The game ends when a player has to draw a card from an empty stack.

Prove that

- \(1-n \leq t_j \leq m \) for all \(j\)

- There exists distinct indices \(i\) and \(j\) such that \(t_i=t_j\)

- Prove that there exists a non empty subset in stack A and another in B such that the sum of the numbers on those cards are equal.

Solution

- If \(t_j\leq 0\), a card from A is removed. The maximum value of a card in A is \(m\) so \(t_j\) can at most be \(m\). Similarly, a card from B is subtracted when the value of \(t_j \geq 1\). Hence, the smallest value it can take is \(1-n\).

- From (1) we see that the \(t\)-sequence can take at most \(n\) distinct non-positive values and at most \(m\) distinct positive values. We consider two ways in which the game can end:

Case 1: Cards in stack B are empty.

Suppose the game ended after using up \(m\) cards from B and \(p\leq n\) cards from A. Since the game has ended the value of \(t_{m+p}\) must be positive. In addition, the value of \(t\) before every card in B was added must have been positive (by the game's rule). So the sequence \(t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots,t_{m+p}\) contains \(m+1\) positive numbers. But since the sequence contains \(m\) distinct positive numbers, two \(t\)s must have the same value by pigeon-hole principle.

Case 2: Cards in stack A are empty.

We use a similar argument. Suppose the game ended after using up \(n\) cards from A and \(p\leq n\) cards from B. Since the game has ended the value of \(t_{n+p}\) must be non-positive. In addition, the value of \(t\) before every card in A was added must have been non-positive. So the sequence \(t_0,t_1,t_2,t_3,\ldots,t_{m+p}\) contains \(n+1\) non-positive numbers. But since the sequence contains \(n\) distinct non-positive numbers, two \(t\)s must have the same value by pigeon-hole principle. - From (2), some \(t_i=t_j\). The sequence of cards added between \(t_i\) and \(t_j\) sums to zero. So some proper subset of \(A\) and \(B\) have equal sums.